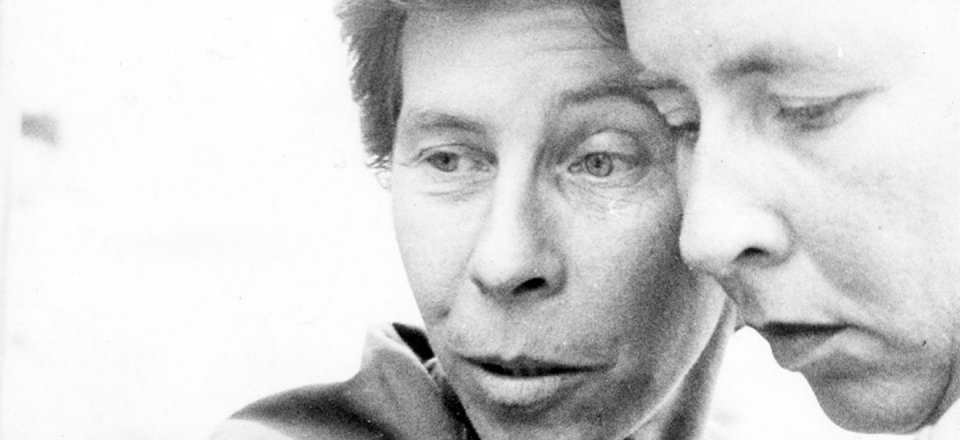

One of the themes of the 2021 Tove Festival in Helsinki was queer themes in Tove Jansson’s literature. Here are some highlights of the discussion focusing on queer Moomin stories – and you can also watch the discussion with English subtitles in the video at the bottom of the article.

What does one actually mean by queer themes in literature? Mia Österlund, Associate Professor in Comparative Literature at Åbo Akademi University, defines queer as something norm-breaking, something that is not in line with the heterosexual norm.

“When you look at fiction, queer can mean different things. It can be a dissonance, an ambivalence – something a bit odd. But it can be something that is very clearly presented as well. That’s how it is with Tove Jansson”, she says.

“I had never thought about Moominvalley as queer”

All three panelists have different personal experiences of discovering queer Moomin stories.

For author Kaj Korkea-aho, finding queer themes in Tove Jansson’s literature was revelatory.

“I had never thought about these things before I became an adult and moved to Turku to study literary science in the early 2000s, and even then it was not talked about much. I mean, that Moominvalley was queer and that Tove Jansson had this side to her.”

Korkea-aho wonders if living in a small city in rural Finland meant being in a “silent zone”.”

“Realising this as an adult and reading the books from this perspective has been very interesting and enriching.”

“As a young, gay man, I understood exactly what she meant”

Mark Levengood, journalist, moderator and Unicef ambassador, has a different experience:

“I am one of those who experienced the queer perspective already in my childhood. Because I grew up in Helsinki [Finland’s capital and Tove Jansson’s hometown]. But it wasn’t that great either in the 70s.”

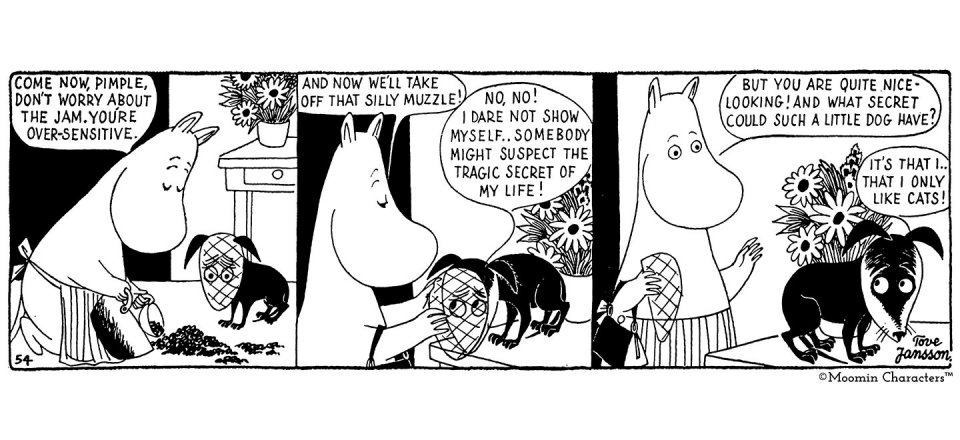

Levengood loved the Moomin comic strips, particularly a story featuring the maid Misabel and her little dog, Pimple, who has to wear a muzzle because he carries a big secret – that he likes cats.

“When you as a very young and very gay young man fumbled around in Helsinki – I understood exactly what she meant. Even though we had no context, and there was nowhere to find this information, I understood her perfectly.”

Moominmamma’s way of addressing the situation with the unhappy dog is very gentle and understanding. Moominmamma first tries to find a cat that wants to be with a dog. When she doesn’t find one, she paints another dog with stripes, so that Pimple gets to play with a “cat”. She never questions Pimple for wanting to play with cats. The attitude, that everything is alright the way it is, is a consistent and carrying theme in Moominvalley.

“My mother was not like Moominmamma, but she had the same attitude”, says Levengood. “When I came out as a sixteen-year-old to my mother, she smoked her cigarette and said: ‘Well, I myself have wondered how it would feel to be with a woman.’

And I said: ‘What! Have you?’ And she answered: ‘No, I just said it to be nice – it would be a lot of fuss.’

Little queer flags for those who can see

“What surprised me is something I call queer typography”, says Mia Österlunnd.

“It means that the first footnote Tove Jansson uses in the Moomin books is about queerness. And it’s about Hemulens. We have a Hemulen who walks around wearing a dress. And the footnote says: ‘The Hemulen always wore a dress that he had inherited from his aunt. I believe all Hemulens wear dresses. It seems strange, but there you are. Author’s note.’

And strange is another word for queer. I see it as she is waving with a little queer flag”, said Österlund.

“That said, I’m exaggerating a little bit”, of course, continued Österlund. “I think Tove Jansson’s poetry is about letting things be. I’m so surprised that she does it so early. She normalizes homosexuality during a time it is forbidden, dangerous. It takes courage to write about it.”

Queer Moomin stories with footnotes

Mia Österlund says there are many of these footnotes – one way to draw attention to the queer perspective. According to her, using footnotes is like adding an exclamation mark, saying ‘something’s going on here!’

“And the fact that it’s a footnote shows that it’s important that the information is there, for the record. But it’s still only a footnote. It’s not something we should pay too much attention to”, adds Kai Korkea-aho.

“That approach is what makes Moominvalley so welcoming and inclusive. Everybody gets to be exactly who they are.”

If you want to read about the part of the panel discussion that focused on Tove’s later literature, but also a very interesting queer reading of Who Will Comfort Toffle, head over to www.tovejansson.com

Watch a longer version of the panel discussion with English subtitles in this video from the festival:

What do the Moomins teach us about loneliness? – Part 1

A postdoctoral researcher, Sanna Tirkkanen, explores what the Moomins can teach us about loneliness, focusing on Moominpappa at Sea.

Mamma will know what to do – How Moomin books comfort us in times of crises, part 1

The first blog of a two-part series, this blog explores how the Moomin books comfort us in times of crises, decades after their creation.

“I’ve fallen madly in love with a woman” – Queer themes in Tove Jansson’s life and work, part 1

In what way was Tove Jansson queer? Explore the diverse gender roles in Moominvalley and the queer themes in Tove Jansson’s art and life.