Tove Jansson: Love, war and the Moomins

This post originally appeared on the BBC’s website and it was written by Mark Bosworth.

This year Finland is celebrating the centenary of the birth of Tove Jansson, creator of the Moomins, and one of the most successful children’s writers ever. Her life included war and lesbian relationships – both reflected by the Moomins in surprising ways.

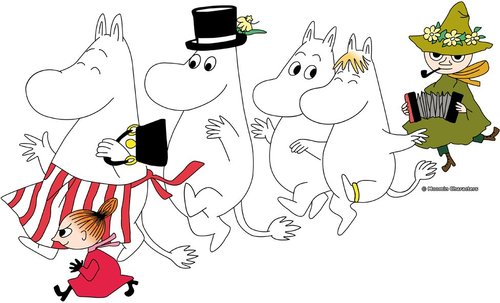

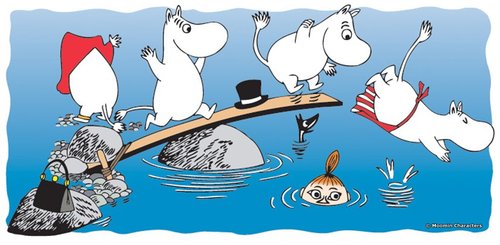

There is Moomintroll, Moominmamma and Moominpappa – little white trolls who live in Moominvalley, with other fantastical creatures such as the Hattifatteners, Mymbles and Whompers.

Tove Jansson’s Moomin books have sold in their millions, and been translated into 44 languages.

Philip Pullman, author of His Dark Materials, has described her as a genius. Other devotees include Michael Morpurgo, writer of War Horse and dozens of other children’s books, and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who scripted the 2012 Olympic opening ceremony.

“I was completely blown away and enchanted,” says Boyce, who read Finn Family Moomintroll as a 10-year-old, after discovering the book in a Liverpool library.

“I didn’t realise it was set in a real place. I thought she’d made Finland up. Finland was like Narnia, with these incredible characters that were so strange but instantly recognisable because you had met lots of them – noisy Hemulens or neurotic, skinny Fillijonks.”

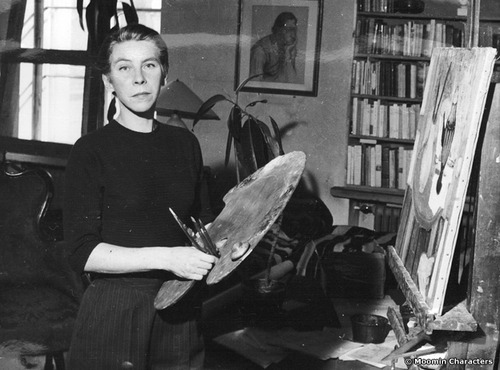

Tove Jansson grew up in an artistic household in Helsinki. Her father, a Swedish-speaking Finn, was a sculptor, her Swedish mother an illustrator.

While her mother worked, Tove would sit by her side drawing her own pictures. She soon added words to the images. Her first book- Sara and Pelle and the Octopuses of the Water Sprite – was published when she was just 13.

She later said that she had drawn the first Moomin after arguing with one of her brothers about the philosopher Immanuel Kant. She sketched “the ugliest creature imaginable” on the toilet wall and wrote under it “Kant”. It was this ugly animal, or a plumper and friendlier version of it, that later brought her worldwide fame.

Jansson studied art in Stockholm and Helsinki, then in Paris and Rome, returning to Helsinki just before the start of World War Two.

“The war had a great effect on Tove and her family. One of her brothers, Per Olov, was in the war. They didn’t know where he was, if he was safe, and if he was coming back,” says Boel Westin, a friend of Jansson’s for 20 years and a Professor of Literature at Stockholm University.

Jansson’s first Moomin book – The Moomins and the Great Flood – was published in 1945, at the end of this difficult and nerve-wracking period, with Comet in Moominland following soon afterwards.

“Tove’s anxiety and grief are embedded in the first two books. She was depressed during the war and this is mirrored in those books because they are about catastrophes,” says Westin.

“Writing a children’s book about a great flood is not so common. In the Comet book, Moomintroll and Sniff go on this journey to find out when the comet is coming and if it’s coming to Moominvalley.

“There are descriptions of creatures leaving their homes. Just like here in Helsinki, people were leaving their homes for fear of the bombs. She captured that and put it in her books.”

The two books went largely unnoticed. Jansson’s breakthrough came in 1951, when her next book – Finn Family Moomintroll – was translated into English.

Two new characters – Thingumy and Bob – appear in the book. The pair represent Tove Jansson and a married woman, Vivicka Bandler, with whom she had a brief and passionate affair. Homosexuality was illegal in Finland at the time, so everything had to be kept secret.

“Thingumy and Bob are always together, walking hand in hand and they have a suitcase but they won’t tell anyone what is in it. It is just referred to as ‘the content’,” says Westin.

Inside the suitcase is a very big and beautiful ruby, a symbol of Tove and Vivicka’s love. The Groke – a large grey, ghost-like creature who freezes everything she touches – is a threat and chases the pair because she is also after love and wants the content.

“You could read this as being the lesbian love between Tove and Vivicka. They have their secret love in this suitcase, and when they open the suitcase and show it to the whole of Moominvalley it is also a picture of how they show their love to the world. It’s a really beautiful story,” says Westin.

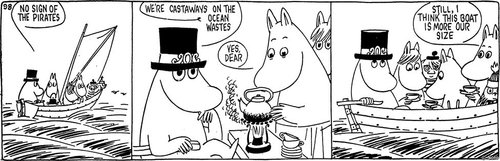

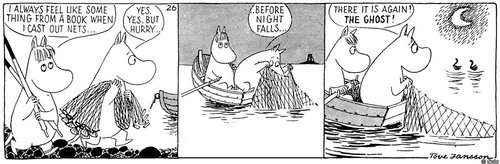

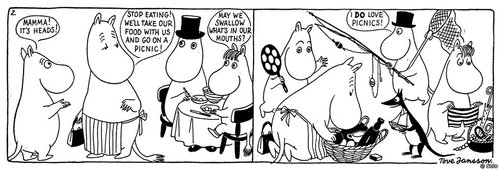

Finn Family Moomintroll’s success caught the attention of Charles Sutton, a London agent who offered Jansson a lucrative deal to produce a Moomin comic strip for London’s Evening News newspaper. Jansson agreed to produce six strips a week for seven years, starting in 1954.

It was an instant hit and within two years 120 newspapers around the world were running it, reaching 12 million readers.

Moomin-mania was now in full swing. Requests for Moomin-related projects came flooding in. Walt Disney asked for exclusive rights to the word “Moomin”, but Jansson refused.

Before long, though, the comic strip started to get her down. She constantly needed new ideas to sustain it, leaving her with little time for painting and writing. “Those damn Moomins,” she wrote in her notes. “I don’t want to hear about them any more. I could vomit on the Moomintrolls.”

Tove Jansson’s creation was taking over her world and, she felt, obscuring her true talents as an artist. To reflect her frustration, she began to draw the Moomintroll bigger and bigger until it dwarfed everything else around it.

In 1956, by the record player at a party, Jansson met a fellow artist, Tuulikki Pietila – or Tooti, as she was known. Jansson asked her to dance. Pietila refused, unwilling to break with social convention. But not long afterwards, Jansson went to Tuulikki’s apartment on a winter’s evening and the pair drank wine and listened to music. They became lifelong partners.

Tuulikki Pietila’s influence on Jansson’s next book, Moominland Midwinter, is not hard to detect.

“Tove introduces a new character into the Moominworld called Too-Ticky and that is Tuulikki Pietila,” says Westin.

“Too-Ticky is the one who gives Moomintroll guidance through the winter and the hard times, so she was really important to Tove. It’s Tooti’s book. It’s a book for her and it’s a book about her.”

The Moomins spend a lot of their time close to water, on boats, or on islands. This was true of the Jansson family too, who used to spend summers on Klovharu, a tiny uninhabited island in the Gulf of Finland.

“They go on excursions to the islands – the Jansson family did exactly that,” says Sophia Jansson, Tove’s niece.

“They went sailing and they went camping on the islands, and if you read the Moomin books there are many things that are, to me, completely normal and to other people are completely fantastical. But in Finland that’s what you do when you are on the islands. That’s what they did and it’s what we’ve always done.”

In 1964, Jansson and Tuulikki Pietila built a simple house on Klovharu, without running water or electricity, which they could escape to in the summer months, and work without interruption.

It was there in 1970 that Jansson began writing her final Moomin book, Moominvalley in November, a melancholy story reflecting the author’s grief after the death of her mother. It features a new character, Toft, which Jansson based on herself. When Toft arrives at the usually busy Moominhouse, there’s no-one there.

The loss of her mother deeply affected Jansson, and the following year she and Pietila embarked on a round-the-world trip. It was at this time that Tove Jansson began writing The Summer Book, her first move into adult fiction.

The book, which centres on the relationship between a six-year-old girl, and her elderly grandmother on an island in the Gulf of Finland, is a barely disguised recreation of the real-world relationship between Jansson’s mother and her grand-daughter, Sophia – also the name of the girl in the book.

“It didn’t feel so odd to read it because fiction and reality get a little bit muddled up when you’re in the Jansson family,” says Sophia Jansson.

“You’re not quite sure what is true and what isn’t true, and does it really matter? Now when I read the Summer Book I feel that it is, by far, the book that is closest to me because it is set on an island I know so well, and so many things in it are so familiar. It really feels like a part of me today.”

Eventually, after spending 28 summers on Klovharu, Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietila – both in their 70s – were no longer fit enough to continue going there.

“Tove realised she had to leave the island when she became scared of the sea. And that was a turning point. She realised she was getting old and frail,” says Sophia.

“Once they left, they didn’t want to speak about it and they didn’t want to go back. They just wanted to keep that period in their minds.”

Tove Jansson died in the summer of 2001, aged 87. Tuulikki Pietila died eight years later.

Since the Moomins and the Great Flood in 1945, more than 15 million Moomin books have been sold, around the world.

Today, Moomin Characters, the company set up by Tove Jansson and her younger brother to deal with image rights, is one of the most profitable companies in Finland – its Helsinki office overlooking the Gulf of Finland populated by cuddly Moomintrolls from the 1950s to the present day.

Most Finnish homes contain some sort of Moomin memorabilia, such as a towel, a children’s plate or an adult’s coffee cup. Their position in national life is such that, over the years, the Finnish post office has issued numerous Moomin stamps. Two stamps bearing Tove Jansson’s portrait were issued in January.

But events to mark Jansson’s centenary are being held far beyond Finland – in the US, Japan and across Europe. The Moomins resonate with children and grown-ups in many countries.

“I lived on this great big housing estate in suburban Liverpool, from a working class background, and somehow this bohemian, upper middle-class, Finnish lesbian eccentric felt like she was speaking directly to me,” says Frank Cottrell Boyce.

“They are just fantastically enriching books. One of the things I really took from them was the importance of small pleasures, that life is really worth living if we’re just nice to each other and make really good coffee, and the pancakes are just right – then nothing else really matters in any substantial way.

“That’s a fantastic message to take home, isn’t it?”